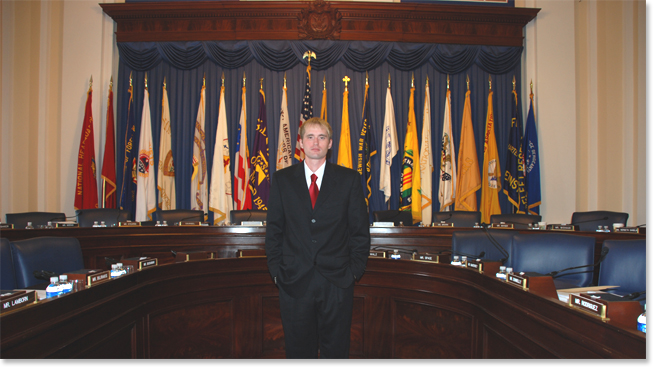

"This is not the way the government ought to work. It's not the way they should be responding to veterans," says Representative Bob Filner, chair of the House Committee on Veterans' Affairs. He first heard Town's story in April and began working soon afterward to bring the soldier to Washington. There Town would get his chance to tell Congress everything: about his diagnosis, his discharge and the work of Surgeon General Pollock.

'Thoroughly Evaluated and Reviewed'

Andrew Pogany, an investigator for the soldiers' rights group Veterans for America, has been looking into personality disorder discharges for two years. The discharge, officially known as Regulation 635-200, Chapter 5-13, is simply a loophole, he says, to dismiss wounded soldiers without providing them benefits. Pogany says Town's case is a textbook example of how Chapter 5-13 is being applied. Town had no history of psychological problems and had served seven years, winning a dozen medals, before being discharged with a personality disorder.

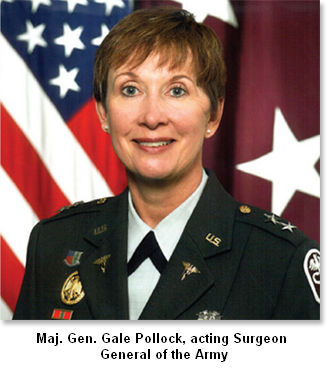

The investigator was so disturbed by the Army's use of 5-13 discharges that he brought his research to Pollock. In late October 2006, he and Steve Robinson, Veterans for America's director of veterans affairs, met with Pollock and presented her with a stack of personality disorder cases, including Town's. The surgeon general promised a thorough review.

On March 23, five months after her meeting with Pogany, Pollock released her findings. Her office had "thoughtfully and thoroughly" reviewed the personality disorder cases and determined that all of the soldiers, including Town, had been properly diagnosed. Pollock commended the doctors who diagnosed personality disorder for their excellent work.

Four days later the military followed up with a press release, this one signed by Lieut. Col. Bob Tallman, the Army's chief of public affairs. Tallman's memo provided further detail on Pollock's review. A panel of behavioral health experts had reviewed the personality disorder cases, Tallman wrote, and they didn't stop at the stack of cases presented to the surgeon general. They "thoroughly evaluated and reviewed" all the Chapter 5-13s from the past four years at Fort Carson, where Specialist Town had been based, and determined that all of those cases had been properly diagnosed as well.

There was a glaring problem with Pollock's review. In the five months she spent "thoughtfully and thoroughly" reviewing the cases, her office did not interview anyone, not even the soldiers whose cases they were reviewing.

Asked how he could call the surgeon general's review "thorough" when no soldiers were interviewed, Tallman said he could not. "Let me be honest with you," he said. "I know nothing about this memo and little to nothing about the review." Tallman said the memo bearing his name was actually ghostwritten by Pollock's office. The lieutenant colonel added that as far as he knew, Pollock conducted no review at all.

Pollock's office quickly admitted that it had ghostwritten the Tallman memo but assured veterans' groups that the surgeon general had indeed conducted a review. In an e-mail Pollock's chief spokeswoman, Cynthia Vaughan, explained that the surgeon general did not want to interview soldiers because she felt they had no medically valid information to share. "Calling a soldier who underwent a 5-13 Chapter in 2003 and asking him (in 2007) to recall his mental condition in 2003 does not hold medical validity," Vaughan wrote.

That statement angered many soldiers, including Jon Town. "You'd think I'd remember, even today, if I had headaches and hearing loss before the rocket attack," he says. The surgeon general tried to quell veterans' groups by emphasizing that, as stated in the March memos, the comprehensive review was conducted by a panel of health experts and that those experts "did not provide the initial evaluations." This wasn't a case of one doctor reviewing his own work, the surgeon general said.

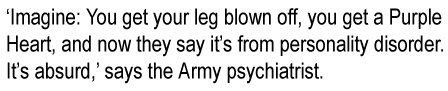

Both of those assurances crumbled on May 4, when Army Times reporter Kelly Kennedy revealed that in fact there was only one reviewer: Col. Steven Knorr. Knorr was a strange choice to be the sole reviewer. He was far from an objective observer. As chief of Fort Carson's Behavioral Health unit, Knorr had overseen all the original diagnoses and, in his capacity as a psychiatrist, also diagnosed several soldiers with personality disorder.

Months earlier Knorr had spoken out in defense of the Army's practice of not interviewing soldiers' family or friends before labeling their condition "pre-existing." Unlike his staff, he said, family members are not trained to recognize signs of personality disorder, so speaking to them would be of limited value. "The soldier's perception and their parents' perception is that they were fine. But maybe they didn't or weren't able to see that wasn't the case."

In the same interview, published in The Nation, Knorr said there was a simple reason why in so many cases the lifelong condition of personality disorder isn't apparent until after troops serve in Iraq. Traumatic experiences, he said, can trigger a condition that has lain dormant for years. "[Troops] may have done fine in high school and before, but it comes out during the stress of service," he said. Knorr's assertion was a sharp break from the accepted medical understanding of personality disorder and provoked a flood of angry letters from psychiatrists and veterans' leaders.

Veterans were further agitated by a vivid profile of Knorr, by NPR's Daniel Zwerdling broadcast in late May. Zwerdling details a memo written by Knorr in which he advises his doctors that trying to save every soldier is a "mistake." "We can't fix every Soldier," the memo states. "We have to hold Soldiers accountable for their behavior. Everyone in life beyond babies, the insane, and the demented and mentally retarded have to be held accountable for what they do in life."

Knorr's memo, which he posted on his office's bulletin board, warns his doctors not to take soldiers' descriptions of their ailments at face value. "We're not naïve, and shouldn't automatically believe everything Soldiers tell us," the colonel writes. Knorr also urges his doctors to discharge troubled soldiers quickly—as he puts it, "Get rid of dead wood."

"That memo made me sick," says Russell Terry, founder of the Iraq War Veterans Organization. "It's incomprehensible that [Pollock] would choose him to lead the review." Terry says that if she had wanted to do a real review, the surgeon general could have organized a panel of impartial medical experts. "By having Knorr review his own stuff, there's no outside opinion, no one to uncover the misdiagnoses—no one to object."

The surgeon general declined to be interviewed. But in a recent statement, Pollock defended her office's review and showed continued support for Knorr, calling him an "appropriate" choice to spearhead the review.

By May the Army had a nascent PR nightmare on its hands. The story of Pollock, Knorr and the "thoughtful and thorough" five-month review had been picked up by news talk programs on NPR, Washington Post Radio and ABC News. To stem the tide, officials at Fort Carson did something odd: They released a new memo stating that fifty-six soldiers discharged from Fort Carson with personality disorder actually had PTSD. By May the Army had a nascent PR nightmare on its hands. The story of Pollock, Knorr and the "thoughtful and thorough" five-month review had been picked up by news talk programs on NPR, Washington Post Radio and ABC News. To stem the tide, officials at Fort Carson did something odd: They released a new memo stating that fifty-six soldiers discharged from Fort Carson with personality disorder actually had PTSD.

It was a stunning admission. As soon as they released it, officials tried to downplay it. Col. John Cho, former commander of Fort Carson's hospital, quickly submitted a second statement, saying that the first memo was not an admission of guilt. Soldiers suffering from PTSD could be rightfully discharged with personality disorder if they had that condition too and their PTSD was not "severe," he said. But Army Regulation 40-501, Chapter 3-33, is clear. It states that if a soldier is suffering from PTSD, he must be discharged by a medical board, which can provide him the lifetime of disability and medical benefits denied soldiers discharged with personality disorder.

Fort Carson officials provided an unintentionally comic coda to their admission when they insisted that all fifty-six cases were properly diagnosed, shortly after Cho admitted in writing that his office could find only fifty-two of them. Base officials said the remaining four cases had been lost or misplaced. They could not explain how they knew those cases were properly diagnosed when they couldn't be found. "It's incredible when you think about it," says Pogany. "They're doing everything they can to cover this up—and doing a lousy job of it."

On May 16, Army officials clarified: The four-year review of personality disorder cases trumpeted in the Tallman memo never occurred.

'I Refused to Diagnose as They Wanted'

By the time Dr. Michael Chen stepped down, he had been serving the Army for more than thirty years. The psychiatrist had treated soldiers at several bases and looked forward to continuing his work at a new installation after being transferred.

Chen's enthusiasm was short-lived. Soon he began clashing with his superiors. "I refused to diagnose as they wanted," he says. "They wanted the diagnoses to be personality disorder, instead of PTSD." The psychiatrist says the soldiers he saw weren't suffering from pre-existing conditions; they had PTSD and traumatic brain injury (TBI). Chen says he relayed this information to his colonel, to no avail. "The establishment wants to hear what the establishment wants to hear."

Chen is not the doctor's real name. Because he fears retribution from the Army, the psychiatrist agreed to speak only if his name and base were not revealed. He says he wasn't the only doctor pressured to misdiagnose: Other psychiatrists were pressed as well, resulting in numerous fraudulent diagnoses of personality disorder. "I've seen that story happen hundreds of times," he says.

While serving at the Army hospital, Chen did diagnose personality disorder. But eventually the absurdity of the recommended diagnoses proved too much. The psychiatrist recalls one soldier who returned from Iraq with a massive hunk of his right calf missing. "They thought he had personality disorder," Chen says, the anger in his voice suddenly palpable. "Imagine: You get your leg blown off, you get a Purple Heart and now they say it's from personality disorder. It's absurd." Frustrated, the psychiatrist approached the commanding general of the hospital. Chen says he met with the official numerous times. But the pressure to misdiagnose continued.

"It's just criminal," he says. The doctor says that at his base wounded soldiers were treated like broken appliances: When they no longer functioned, the command simply wanted to "throw them out" with a pre-existing condition. "And it's appalling to me that my colleagues would go along with it."

The psychiatrist says he doesn't blame the commanding general for the pressure on him and other doctors to misdiagnose soldiers. Their meetings made it clear that the general was simply taking orders from "high up on the food chain." In some sense, says the doctor, that was to be expected, because with personality disorder, there's so much money at stake. The Nation reported in April that the military is saving $12.5 billion in disability and medical care by discharging soldiers under Chapter 5-13, a figure drawn from a recent Harvard study by Professor Linda Bilmes. Chen believes $12.5 billion is a gross underestimate—that from what he's seen at his medical center, if all the wounded soldiers returning from Iraq were properly diagnosed, the long-term cost of benefits would be exponentially larger.

As it was, says Chen, the medical ethic at the Army hospital followed the guidelines of the Knorr memo, which urged doctors not to take soldiers' descriptions of their ailments at face value. The psychiatrist's own approach was radically different. "If a soldier said he had PTSD, I wrote up 'PTSD.' Finally I was told I couldn't see any more soldiers because I diagnosed PTSD too much." Chen left the hospital soon after. Today he treats patients at a nonmilitary facility.

Dr. Brian Harrison still works for the military. Like Dr. Chen, his years as an Army psychiatrist have been contentious. Harrison says that at his medical center, "there has been a tradition of 'underdiagnosing.'" That means soldiers with PTSD don't always receive that diagnosis. And their health isn't always the top concern. Foremost on the command's mind, says Harrison, is getting soldiers back to Iraq. He says doctors at his base understand that when wounded soldiers seek treatment from them, their job is to get the soldiers back to the battlefield, even if they are traumatized. The psychiatrist quotes his hospital's chief of Behavioral Health as saying, "If they're not suicidal or homicidal, they're fit to go back." If they don't meet that standard, the doctors are to get rid of them fast. Wounded soldiers are "seen as damaged merchandise," Harrison says. "The command wants people like that out of their hair, out of their way."

Harrison is also a pseudonym. The doctor says he is speaking out in violation of an e-mail from his superiors ordering psychiatrists at his facility not to talk to the media. If he gives his name, he says, he could be fired. Harrison is also a pseudonym. The doctor says he is speaking out in violation of an e-mail from his superiors ordering psychiatrists at his facility not to talk to the media. If he gives his name, he says, he could be fired.

The doctor says he has never been pressured to misdiagnose. The biggest challenge he has faced is making a correct diagnosis, given the brevity of his appointments. Until recently, he was allowed to meet with soldiers for an hour. But now, he says, the chief of his department has pressed him to cut his evaluation time to half an hour and make future appointments between fifteen and thirty minutes. "I can't do an evaluation in half an hour," says the psychiatrist. "To properly diagnose a soldier, you need at least an hour." Like Chen, Harrison doesn't blame his department's chief, noting that there's pressure on him from his superiors—"the money managers," Harrison calls them. "Those jackasses—they don't have any clinical experience, they've never worked with soldiers, and they don't care."

The bitterness in his voice is broken suddenly with a warm laugh. "Maybe I'm just old-fashioned," says the elderly doctor. Harrison has been practicing psychiatry for almost forty years and still insists on some decidedly "old-fashioned" techniques, like interviewing soldiers' families when diagnosing a pre-existing condition to see whether the soldiers' troubles existed before joining the service. Other doctors at the Army hospital "don't make any effort to do that," he says. "And they don't have time to. They're busy herding people through."

Surgeon General Pollock declined to comment on Chen's and Harrison's allegations. In a statement, she says she is disturbed by the idea that "individuals [are] pressuring providers to falsify diagnoses.... Such conduct, of course, would be totally unacceptable." Pollock advises doctors who feel under pressure to diagnose personality disorder to contact the Inspector General. She asks soldiers who feel they have been misdiagnosed to approach her directly. Due to "my concern over these issues, they may provide their information to me and I will have the staff review their records."

Flying Blind

In May, before most in Washington had even heard of Chapter 5-13, Senator Kit Bond was studying the discharge—and calling for its abolition. "You have 22,000 soldiers who passed through all the tests required to send them to Iraq, and they came back and were diagnosed with a pre-existing condition? It just doesn't compute. We need to fix the system," he says. "They ought not have the 5-13 as an easy way to put these soldiers out." As the system is now, the Senator says, some of the cases he's seen "just scream out to me: 'This person was railroaded.'"

The Republican from Missouri helped put together a coalition of thirty-one senators spanning the political spectrum, from Hillary Clinton to Joseph Lieberman to fellow conservative Elizabeth Dole. In June they wrote a letter to Defense Secretary Robert Gates requesting that he investigate the 5-13 discharge process. Bond also co-wrote a defense authorization amendment with Senator Barack Obama and others that would put a temporary freeze on all personality disorder discharges. The amendment has been referred to the Armed Services Committee.

The past year has exposed several problems in the way we're treating veterans, says Bond. "And this 5-13 seems to be a major part of the problem."

By July the Senate wasn't the only organization in Washington concerned about personality disorder. The Department of Veterans Affairs was worried too. "We wanted to prioritize injured [Iraq War] veterans. We want to provide a seamless transition" from the Army, says a top VA official. But with these personality disorder discharges, "you have people now falling through the cracks." The official, who demanded anonymity because he had not received clearance to speak, says the problem with phony discharges like personality disorder is that they short-circuit the VA's Red Flag system.

The Red Flag system is an informal name for the VA's method of identifying the most wounded soldiers. The agency does this, explains the official, by keeping its eye on the Army's medical board hearings, where wounded soldiers are supposed to go before their discharge. The board evaluates injured soldiers and gives them a disability rating. Under the Red Flag system, those who leave the Army's medical board hearings with a high disability rating are flagged and targeted for immediate medical care.

But soldiers discharged with personality disorder are denied the opportunity to see a medical board and thus don't get a disability rating. As a result, they fly under the VA's radar. Those who need immediate medical care get dumped into the stack of 800,000 cases currently waiting to be processed by the VA. For the VA to function, says the official, the Army has to pass wounded soldiers through its medical boards. Otherwise, the agency is flying blind.

Jon Town knows firsthand the price of that blindness. He submitted an application for VA medical care shortly before leaving the Army. Seven months later he was still waiting for his first doctor's appointment. Jon Town knows firsthand the price of that blindness. He submitted an application for VA medical care shortly before leaving the Army. Seven months later he was still waiting for his first doctor's appointment.

Without medical treatment, Town struggled alone with deafness, memory loss, insomnia and a headache that was still raging three years after the rocket attack. The specialist tried to take a few jobs, but each time he was fired after his health proved too much of an issue. His wife, Kristy, had to keep the family of four afloat with her minimum-wage job on the assembly line at Filtech, an oil-filter manufacturer in their hometown of Findlay, Ohio. Soon the family was teetering on the verge of bankruptcy. In May, the phone company shut off their service because the Towns couldn't pay their bill.

The media took note. In April came the Nation article, followed by the Law & Order episode, which introduced Town's story to 9 million viewers. When musician Dave Matthews saw the article and began discussing it in concerts, his enraged fans took up a collection for Town, which raised $3,000. The guitarist followed up by posting a petition on his website, urging Congress to hold hearings on personality disorder. Within weeks the petition was signed by 23,000 people.

"There are times when an injustice is so clear, it's not a matter of opinion," says Matthews. "Nobody would argue that what's happening to Jon Town is right. And to think that it's happening over and over again...it's just astounding. It's a crime against these young people that's so profound—and it's happening right now. I had to ask myself, 'Does America think this is OK?'" People won't think it's OK once they learn what's going on, says Matthews. "We can fix this catastrophe. It's just a matter of getting people to know about it."

Soon Nation readers, NBC viewers and Matthews fans were reaching out to Town en masse: e-mails, phone calls, small personal checks. The local chapter of Veterans of Foreign Wars organized a motorcycle ride to honor his service. A veteran from Boston offered Town his disability pay until the specialist could secure his own.

Strangely enough, Town's big break came not from Matthews, NBC or even Senator Bond but from Lou Wilin, a reporter at the Findlay Courier, Town's hometown paper (circulation 23,000). After reading Town's story in The Nation, Wilin wrote a profile of the soldier, which ran in the newspaper's April 16 edition. The article caught the eye of an admiral in the VA who happens to live a few miles east of Findlay. The admiral flagged Town's case, kicked it to the Cleveland VA, which passed it to the Dayton VA, where case manager Janine Wert was ready to take action. Wert received Town's case the morning of April 19 and had the soldier in her office before the end of lunch. She listened to his story and cried.

"His childhood, high school and military history—none of it supports a personality disorder. When you're a teenager, there are certain things that pop up that are vividly obvious, red flags for personality disorder. Those aren't present in Jon's history," says Wert, a social worker with a master's degree in mental health. Wert says Town's PTSD and TBI symptoms were obvious from their first meeting. She was struck by the absurdity of the Army's diagnosis. "I have never in my life heard of personality disorder causing deafness," says the counselor.

Wert arranged an immediate doctor's appointment for Town and scheduled an evaluation by a VA medical board. On June 11 the VA ruled that Town was in fact wounded in combat. The agency declared him 100 percent disabled.

Town's VA rating guaranteed him disability and medical benefits for the rest of his life. The VA also provided the disability pay that Town should have received in the months following his discharge. On June 25, just weeks after his family's phone had been shut off, the specialist received a check for $20,000.

"I almost started to cry," says Town. "They were ready to repossess everything. And now I knew we weren't going to lose our cars to bankruptcy, that we'd have food on the table for years to come.... There isn't a word for what I was feeling."

The diagnosis was a remarkable victory for the Town family—and a pointed defeat for the Army, which to this day insists that Town was not wounded in combat and that his health problems stem from a personality disorder. He still has not received any of the benefits owed him by the Army.

"This is a scandal," Representative Filner said in May. And members of his VA Committee would be interested in pursuing it, "but right now, they just don't know anything about it." With the uproar about Town, Filner saw an opportunity to change that. On July 12 he announced that his committee would hold a hearing on personality disorder. To do it right, he said, "we definitely want to hear from soldiers."

Filner had a particular soldier in mind.

'This Would Be Wrong'

July 25. By 10 am, it's standing room only at the Cannon House Office Building, the hearing room swimming with men in uniform, veterans with camouflage accessories, protesters in bright pink sporting handwritten placards demanding justice for soldiers. A row of photographers crouch beside the CBS News camera; reporters for ABC News, NPR and the New York Times have set up shop behind the soldier at the witness desk.

Not surprisingly, Town didn't sleep the night before. His headache is still raging; his eyes look a bit bloodshot. But his blond bangs are combed, and his favorite red-striped Old Navy shirt is gone, as is the brown ball cap and reflective sunglasses, replaced with a well-pressed navy suit and crimson tie. Town holds his dog tags in his hand and rubs them nervously between his thumb and forefinger as he looks up at the committee, his voice defiant and jittery.

"I want to state that I did not have a personality disorder before I went into the Army, as they have stated in my paperwork. I did not suffer severe nonstop headaches. I did not have memory loss. I did not have endless, sleepless nights. I have posttraumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury now due to the injuries I received in the war, for which I received a Purple Heart," he says. "I shouldn't be labeled for the rest of my life with a personality disorder, and neither should my fellow soldiers who also incorrectly received this stigma."

Filner looks down at the specialist with paternal eyes. When the applause dies down he says, "Thank you, Mr. Town. You did not sign up to have to do this. But you are helping a lot of people, and we thank you for your courage."

Two hours later Surgeon General Pollock's psychological consultant, Col. Bruce Crow, sits at the witness desk. Pollock herself was called to testify; her name appeared on the original witness list. But today she's nowhere to be found, a fact that angers several of the Congressmen. Speaking in her stead, Crow says, "Questions have been raised about whether Army psychiatrists and psychologists are misdiagnosing soldiers with personality disorder instead of correctly diagnosing PTSD or traumatic brain injury." If they are misdiagnosing soldiers, says Crow, "this would be wrong."

Pollock's consultant says that the surgeon general is reviewing the cases of 295 soldiers discharged with personality disorder. Pollock will conduct the review, says Crow, by having "a team of senior mental health providers" look over the soldiers' paperwork.

Filner shakes his head, baffled. "The first panel shocked me," says Filner, referring to Town's testimony. "You guys shocked me even more." The allegation "that there's a systematic and policy-driven misdiagnosis of PTSD as personality disorder to get rid of soldiers early, to prevent any expenditures in the future, which were calculated in the billions of dollars...it's a pretty serious allegation." Crow looks back at Filner. He says nothing. "And if you think that we're going to believe an evaluation of 295 cases, whichever ones you happen to pick—that we're going to believe what you say—I'll tell you now, I'm not going to believe it. So why bother?" says the chairman. "Let's have an independent evaluation."

When the hearing ends, Crow exits. Several Congressmen walk toward the gallery to shake Town's hand. The hearing went well, says the soldier. He was glad to hear support on both sides of the aisle for the Bond/Obama amendment to freeze 5-13 discharges and its companion legislation in the House, HR 3167, put forward by Congressman Phil Hare and others.

Now that Town has gotten his VA benefits, his eye has turned toward the national issue of 5-13 discharges. That is where there's a lot of work left to be done, he says. Town points out that still today, not a single person has been held responsible for the 5-13 discharges—not Surgeon General Pollock, not Colonel Knorr, not even the Army psychologist who diagnosed his personality disorder, Dr. Mark Wexler.

And there hasn't been any effort to go back through the files and find the thousands of Jon Towns who are struggling right now without benefits or the media spotlight. "The Army needs to go back and find these guys," says the specialist. "They need to show up and say, 'We apologize—and we're here to rectify the situation.'"

Until that happens, he says, his work is not done.

|