wounded during service. Soldiers discharged with PD are also denied long-term medical care. And they have to give back a slice of their re-enlistment bonus. That amount is often larger than the soldier's final paycheck. As a result, on the day of their discharge, many injured vets learn that they owe the Army several thousand dollars.

According to figures from the Pentagon and a Harvard University study, the military is saving billions by discharging soldiers from Iraq and Afghanistan with personality disorder.

In July 2007 the House Committee on Veterans' Affairs called a hearing to investigate PD discharges. Barack Obama, then a senator, put forward a bill to halt all PD discharges. And before leaving office, President Bush signed a law requiring the defense secretary to conduct his own investigation of the PD discharge system. But Obama's bill did not pass, and the Defense Department concluded that no soldiers had been wrongly discharged. The PD dismissals have continued. Since 2001 more than 22,600 soldiers have been discharged with personality disorder. That number includes soldiers who have served two and three tours in Iraq and Afghanistan.

"This should have been resolved during the Bush administration. And it should have been stopped now by the Obama administration," says Paul Sullivan, executive director of Veterans for Common Sense. "The fact that it hasn't is a national disgrace."

On Capitol Hill, the fight is not over. In October four senators wrote a letter to President Obama to underline their continuing concern over PD discharges. The president, almost three years after presenting his personality disorder bill, says he remains concerned as well.

Veterans' leaders say they're particularly disturbed by Luther's case because it highlights the severe consequences a soldier can face if he questions his diagnosis and opposes his PD discharge.

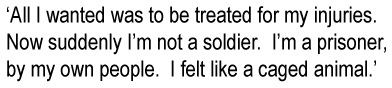

Luther insisted to doctors at Camp Taji that he did not have personality disorder, that the idea of developing a childhood mental illness at the age of 36, after passing eight psychological screenings, was ridiculous. The sergeant used a vivid expression to convey how much pain he was in. "I told them that some days, the pain was so bad, I felt like dying." Doctors declared him a suicide risk. They collected his shoelaces, his belt and his rifle and ordered him confined to an isolation chamber.

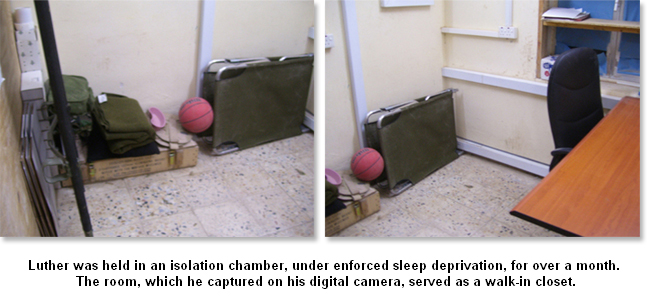

Extensive medical records written by Luther's doctors document his confinement in the aid station for more than a month. The sergeant was kept under twenty-four-hour guard. Most nights, he says, guards enforced sleep deprivation, keeping the lights on and blasting heavy metal music. When Luther rebelled, he was pinned down and injected with sleeping medication.

Eventually Luther was brought to his commander, who told him he had a choice: he could sign papers saying his medical problems stemmed from personality disorder or face more time in isolation.

'Every Night It Was Megadeth'

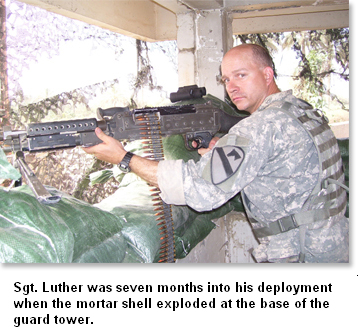

Luther entered the Army in 1988, following in the footsteps of his grandfathers, both decorated World War II veterans. In 2005, after Hurricane Katrina, he and his unit were deployed to New Orleans, where he helped evacuate residents and dispose of bodies left in the street. In 2006 he was deployed from Fort Hood in Texas to Camp Taji, where he performed reconnaissance with the First Squadron, Seventh Cavalry Regiment, led by Maj. Christopher Wehri. "Luther was older and more mature than most of the soldiers. He was forthcoming, very polite," says Wehri. "He seemed to have a good head on his shoulders."

Doctors at the aid station didn't see him that way. Following the May 2007 mortar attack, Luther entered the base's clinic and described his concussion symptoms to Capt. Aaron Dewees. Dewees, a pediatrician charged with caring for soldiers in the 1-7 Cavalry, grew suspicious of Luther's self-report. "It is my professional opinion," Dewees wrote in his medical records, "that Sgt. Charles F. Luther Jr. has been misrepresenting himself and his self-described medical conditions for secondary gain." The doctor suggested that Luther was faking his ailments to avoid reconnaissance duty. He called the sergeant "narcissistic" and said Luther's descriptions of his injuries were a mixture of "exaggeration and flat-out fabrication." Doctors at the aid station didn't see him that way. Following the May 2007 mortar attack, Luther entered the base's clinic and described his concussion symptoms to Capt. Aaron Dewees. Dewees, a pediatrician charged with caring for soldiers in the 1-7 Cavalry, grew suspicious of Luther's self-report. "It is my professional opinion," Dewees wrote in his medical records, "that Sgt. Charles F. Luther Jr. has been misrepresenting himself and his self-described medical conditions for secondary gain." The doctor suggested that Luther was faking his ailments to avoid reconnaissance duty. He called the sergeant "narcissistic" and said Luther's descriptions of his injuries were a mixture of "exaggeration and flat-out fabrication."

Luther's medical records document severe nosebleeds and "sharp and burning" pain. Still, the sergeant says he could sense that his doctors didn't believe him. It was at that point—frustrated, plagued by blinding migraines—that he spoke of pain so severe he wished he were dead. "I made clear that I was not going to kill myself, that it was just a colorful expression to explain how much pain I was in." Dewees agreed. In their records, Luther's doctors note a "suicide gesture" and "'off-handed' comments" that the sergeant was going to kill himself, but Dewees said those gestures were "unlikely to have been a serious attempt" at self-harm. Nonetheless, Dewees wrote, such statements "must be taken seriously and treated as such," that Luther "remains a threat to himself and others given his need for attention, narcissistic tendencies and impulsive behavior."

Luther was taken to an isolation chamber and told this was his new sleeping quarters. The room, which Luther captured on his digital camera, served as a walk-in closet. It was slightly larger than an Army cot and was crammed with cardboard boxes, a desk and a bedpan. Through a small, cracked window, he could look out onto the base. Through the open doorway, the sergeant was monitored by armed guards.

Both Dewees and Lt. Col. Larry Applewhite, an aid station social worker, declared Luther mentally ill, suffering from a personality disorder. The next step was to remove him from the military as fast as possible. "It is strongly recommended that Sgt. Luther be administratively separated via Chapter 5-13," wrote Applewhite, citing the official discharge code for personality disorder. In a separate statement, Dewees endorsed the 5-13 discharge and urged that it be handled rapidly. "I feel the safest course of action," he wrote, "is to expedite his departure from theater."

That didn't happen. For more than a month Luther remained in his six-by-eight-foot isolation chamber, weeks he describes as "the hardest of my life." He says the guards would ridicule him and most nights enforced sleep deprivation, keeping the lights on all night and using a nearby Xbox and TV speakers to blast heavy metal into his room. "Every night it was Megadeth, Saliva, Disturbed." The sergeant pulled a blanket over his head to block out the noise and the light, but it was no use.

"They told me I wasn't a real soldier, that I was a piece of crap. All I wanted was to be treated for my injuries. Now suddenly I'm not a soldier. I'm a prisoner, by my own people," says Luther, his voice tightening. "I felt like a caged animal in that room. That's when I started to lose it."

Isolated, exhausted, the sergeant who had been confined for being mentally ill says he began feeling exactly that. Finally Luther snapped. He stepped out of his room and was walking toward a senior official's office when an altercation broke out. In the ensuing scuffle, Luther bit one of his guards, then spit in the face of the aid station chaplain. The sergeant was pinned to the floor and injected with five milligrams of Haldol, an antipsychotic medication. Sedated, Luther was returned to isolation.

Staff Sgt. James Byington, who was serving at Camp Taji with the 1-7 Cavalry, walked the half-mile to the aid station to visit his fellow soldier. Byington says that off the battlefield, Sergeant Luther was "animated and peppy," the comedian of the chow hall. During combat, he says, Luther was focused and prepared, a key component in a farmland raid just outside Taji that discovered a cache of weapons and money. The man he found in the isolation chamber was neither the soldier nor the comedian, he says, but something altogether odd and decrepit. "He wasn't energetic like he used to be. He wasn't cutting jokes. Chuck's one of those guys that talks with his hands. You go into a room with twenty guys, and you're going to hear Chuck Luther," says Byington. "Now he seemed half-asleep. He looked worn out."

A few hours after Byington's visit, Luther was called to his commander's office. Major Wehri was frank. He held the personality disorder discharge papers in his hand. "And he said, 'Sign this paperwork, and we'll get you out.' I said, 'I don't have a personality disorder.' But it was like that didn't matter," says Luther. "He said, 'If you don't sign this, you're going to be here a lot longer.'"

The sergeant signed. "They had me broke down," he says. "At that point, I just wanted to get home." Luther's voice grows quiet as he recounts that final meeting. "I still remember Wehri's face," he says. "He was smiling."

Wehri confirms his statements to Luther. He says he pressed the sergeant to sign because he felt it was in Luther's best interest and in the best interest of the Army. The sergeant, he says, "had gotten so belligerent. If we had returned him to his unit, he would have been a danger to himself and to others. His behavior was not suitable to military service. And he wanted to get home. So I told him, 'If your goal is to get home, and we've diagnosed you with personality disorder, your fastest way is to sign the papers. If you don't sign, you're just subjecting yourself to further anguish and discomfort.'"

Wehri insists that his comments to Luther were not pivotal to the sergeant's discharge. Even without a soldier's signature, a PD dismissal can proceed. But the papers would then move to an Army lawyer, and the process would be delayed. "You can't force anyone to sign," he says. "But if you're going to be stubborn and not sign, try to play hardball, you run the risk of a dishonorable discharge. With Luther's biting and spitting, I could have court-martialed him out right there for failure to perform in a military manner."

The major says Luther's real story is that of a good soldier who came home for leave, saw his wife's new haircut and slimmed figure and was driven mad by fears of her infidelity. "When he came back to Iraq, something had changed. He had a negative attitude. He wouldn't respond to direct orders. His head wasn't in the game." Wehri says it became clear to him that Luther was intent on returning home right away, a realization that left him disappointed but not shocked. "Soldiers are conniving," he says. "They are manipulative. If they get in their minds they want to do something for personal gain, including going home, they'll go to any lengths to get it."

Wehri rejects the idea that the mortar attack and subsequent concussion could have triggered Luther's woes. "That mortar attack was nothing," he says. "Insignificant. Maybe he fell down. Sure. I've fallen down lots of times." The major wonders aloud whether Luther is using that injury to justify his instability. He says if he thought the attack was significant, he would have investigated it fully and gotten the ball rolling for a Purple Heart.

The major confirms that Luther was confined to the aid station for several weeks and that his room was minuscule. But he says those circumstances were unavoidable. "Discharging a soldier with personality disorder is a very long and drawn-out process," he says. "And Luther was a danger to himself and others. He needed to be watched. The aid station, that's where they had 24-7 supervision."

Wehri says he marvels at the idea that Luther could be a poster child for false personality disorder discharges. He has seen seven personality disorder cases in his career, he says. "And Chuck Luther was by far the clearest one." The major says that when Luther's troubles began, the sergeant's behavior confounded him. Then, says Wehri, he heard from a commander who said Luther's family had spoken with him and revealed that Luther had suffered from psychiatric problems before entering the military and had been treated with medication. "Then suddenly it made sense to me," says Wehri. "This was not new. His symptoms were just popping up now, after he'd kept a lid on them for many years. It all clicked into place."

But Luther's wife and his mother say that story is flatly false. Both say they never had such a conversation with an Army commander and are emphatic that the sergeant never faced any psychiatric problems before entering the military. "Hearing that makes me really angry," says Luther's mother, Barbara Guignard. "Chuck was an all-American boy. He never took any medication, and he never had a problem."

How Dewees and Applewhite came to the conclusion that Luther was suffering from a pre-existing mental illness remains unclear. They declined to elaborate on their notes or discuss the diagnosis of personality disorder in general. What is clear is that neither Dewees nor Applewhite spoke with Luther's family before determining that his problems existed before his military service. The sergeant's wife and his mother say that had they been asked, both could have provided key information demonstrating Luther's stability and health before the mortar attack. How Dewees and Applewhite came to the conclusion that Luther was suffering from a pre-existing mental illness remains unclear. They declined to elaborate on their notes or discuss the diagnosis of personality disorder in general. What is clear is that neither Dewees nor Applewhite spoke with Luther's family before determining that his problems existed before his military service. The sergeant's wife and his mother say that had they been asked, both could have provided key information demonstrating Luther's stability and health before the mortar attack.

Spc. Angel Sandoval says he could have helped as well. Sandoval, who was stationed at Camp Taji and served under Luther in the 1-7 Cavalry, laughs at the idea that the sergeant was mentally ill. "Chuck was a lot more than 'not mentally ill,'" he says. "He saved my life." Sandoval describes heading into combat under Luther's command. The specialist was ready to dump his side-SAPIs, large ceramic plates that strap to the side of a bulletproof vest, protecting the kidneys from machine-gun fire. "They're bulky and kinda heavy, but he said, 'No way, you have to wear them,'" says Sandoval. "Two days later I got shot right there, under my arm. It could have killed me."

Luther, he says, was "one of the greatest leaders I had. He never steered me wrong. If they thought he was ill and needed medical help, they should have given it to him instead of kicking him out of the Army."

But it was Wehri and Applewhite's view that mattered. Soon after signing the personality disorder papers, Luther was placed in a DC-10 and whisked back to Fort Hood. There he would learn about Chapter 5-13's fine print: he was ineligible for disability benefits, since his condition was pre-existing. He would not be receiving the lifetime of medical care given to severely wounded soldiers. And because he did not complete his contract, he would have to return a slice of his signing bonus.

At the base, a Fort Hood discharge specialist laid out the details. "He said I now owed the Army $1,500. And if I did not pay, they'd garnish my wages and assess interest on my debt," Luther says.

Luther was then released into a pelting Texas rain. He called his wife, Nicki, to pick him up. "When I got to Fort Hood he was in the parking lot, alone, wet, sitting on his duffel bag," Nicki recalls. "He had lost a lot of weight. He looked like...a little boy. I remember thinking, My God, what have they done to my husband?"

The President 'Continues to Be Concerned'

Luther's case is not an isolated incident. In the past three years, The Nation has uncovered more than two dozen cases like his from bases across the country. All the soldiers were examined, deemed physically and psychologically fit, then welcomed into the military. All performed honorably before being wounded during service. None had a documented history of psychological problems. Yet after seeking treatment for their wounds, each soldier was diagnosed with a pre-existing personality disorder, then discharged and denied benefits.

That group includes Sgt. Jose Rivera, whose hands and legs were punctured by grenade shrapnel during his second tour in Iraq. Army doctors said his wounds were caused by personality disorder. Sailor Samantha Stitz fractured her pelvis and two bones in her ankle. Navy doctors cited personality disorder as the cause. Spc. Bonnie Moore developed an inflamed uterus during her service. Army doctors said her profuse vaginal bleeding was caused by personality disorder. Civilian doctors disagreed: they performed emergency surgery to remove her uterus and appendix. After being discharged and denied benefits, Moore and her teenage daughter became homeless.

"The military is exacerbating an already bad situation," says Sullivan of Veterans for Common Sense. "This is more than neglect. It's malice." Sullivan's organization has spent the past few years pressing officials in Washington to take action on the personality disorder issue. In July 2007 he testified before the House Committee on Veterans' Affairs. Sullivan told the committee that PD discharges needed to be halted immediately.

That month Obama put forward his bill to do just that. The bill was matched in the House by legislation from Representative Phil Hare, and it had passionate support on both sides of the aisle, from prominent Democrats like Senator Barbara Boxer to high-ranking Republicans like Senator Kit Bond. Sullivan and other veterans' leaders say they were hopeful that Obama would use the spotlight of the presidential campaign to generate further momentum for his bill.

That didn't happen. In the twenty-one months of his presidential run, the Illinois senator never spoke publicly about PD discharges or his bill to halt them. Eventually, without widespread public knowledge or support, and facing opposition from senators who had never heard of personality disorder and worried the bill would open a floodgate of expensive benefits, Obama and Bond, the bill's co-author, were forced to reshape it into an amendment and water down its contents. Their amendment did not halt PD discharges. Instead, it required the Pentagon to investigate PD dismissals and report back to Congress. The amendment, part of the Defense Authorization Act, was signed by President Bush in January 2008.

Five months later the report landed on Obama's and Bond's desks. The Pentagon's conclusion: no soldiers had been improperly diagnosed, and none had been wrongly discharged. The report praises the military's doctors as "competent professionals" and endorses continued use of pre-existing personality disorder to discharge soldiers whose "ability to function effectively" is impaired. The report's author, former Under Secretary of Defense David Chu, further notes that though the Navy's official label for the discharge is "Separation by Reason of Convenience of the Government," soldiers "are not wantonly discharged at the convenience of the Military." Five months later the report landed on Obama's and Bond's desks. The Pentagon's conclusion: no soldiers had been improperly diagnosed, and none had been wrongly discharged. The report praises the military's doctors as "competent professionals" and endorses continued use of pre-existing personality disorder to discharge soldiers whose "ability to function effectively" is impaired. The report's author, former Under Secretary of Defense David Chu, further notes that though the Navy's official label for the discharge is "Separation by Reason of Convenience of the Government," soldiers "are not wantonly discharged at the convenience of the Military."

It is unclear how Chu came to these conclusions. The report does not cite any interviews with soldiers discharged with personality disorder, or their families, doctors or commanders. That fact infuriated many military families, as it triggered memories of a 2007 study by former Army Surgeon General Gale Pollock. Pollock had been asked to examine a stack of PD cases. Five months later she released her report, saying her office had "thoughtfully and thoroughly" reviewed them. Like Chu, she commended the soldiers' doctors and determined that they all had been properly diagnosed. The Nation later revealed that Pollock's office did not interview anyone, not even the soldiers whose cases she was reviewing.

"He doesn't talk to soldiers, and he doesn't talk to their families?" says Nicki Luther, the sergeant's wife, her eyes welling with tears. "I heard the same thing from that surgeon general, and I thought, You haven't been in my house. You don't know what I've dealt with. How dare you sit there and say you've investigated thoroughly and found nothing. That's a crock."

The Chu report does recommend several changes to the PD discharge system, alterations, it says, that will protect soldiers from being wrongly discharged. Those protections include requiring that a doctor diagnose the soldier's personality disorder and a lawyer counsel him on the ramifications of the discharge. The report also recommends that the surgeon general review each soldier's case and endorse the PD discharge before releasing the soldier from the military.

Chu, a Bush appointee, left office in 2008 with the president. But his findings remain as the Defense Department's position on PD discharges. In early April the Pentagon released a statement saying that Clifford Stanley, the current under secretary, is implementing Chu's recommendations and fully embraces his findings.

That fact left many on Capitol Hill enraged. "This study, with the new requirement to have the upper-ups approve discharges—all it basically did was set up one more hurdle. As far as we can tell, the impact has been somewhere between zero and less," says Senator Bond. Bond says the Pentagon still hasn't explained the fundamental contradiction of a PD discharge: recruits who have a severe pre-existing mental illness could not pass the rigorous screening process and would not be accepted into the military in the first place. Yet he says his office is looking at several cases, like Luther's, in which the soldiers have been deemed physically and psychologically fit in several screenings before their personality disorder is diagnosed. "These men and women who have put their lives on the line, we owe them," says Bond. "We have a responsibility. Discharging them with personality disorder—it's just an easy way to duck that responsibility."

The Republican from Missouri says he's hopeful that Obama, his partner on the PD bill, will take action from the White House. "He has a unique chance now to change the whole operation, to alter the system from the inside." In October Bond gathered a small coalition of senators and wrote a letter to the president, asking him to confront the issue once again. "In 2007 we were partners in the fight against the military's misuse of personality disorder discharges," wrote the senators. "Today, we urge you to renew your commitment to address this critical issue."

The next week Senator Boxer, a co-sponsor of the original bill, submitted a statement of her own. "It is simply appalling that any combat veteran with a Traumatic Brain Injury [TBI] or Posttraumatic Stress Disorder would be denied medical care for injuries sustained during combat," Boxer wrote. Even with the reforms that followed the Chu report, "we must make sure that the new discharge process...is working."

The White House responded quickly, assuring the senators that the president still has his eye on personality disorder. President Obama "is determined to fulfill America's responsibility to our Armed Forces," says White House spokesman Nicholas Shapiro. "The president was concerned with personality disorder discharges as a senator, and he drafted a bill. He continues to be concerned as commander in chief."

Disposable Warriors

Luther hopes that concern will translate into action. The sergeant stands in his backyard, 1,500 miles from Washington, five miles from Fort Hood, talking about Obama's bill and watching his 7-year-old daughter floating high above the family's oversize trampoline, her face wild with joy. Luther looks on with sullen eyes. "Right now I can't worry about Washington, or even about fixing my discharge papers," he says. "First thing, I got to fix myself." He gestures to his daughter, a mop of blond hair leaping to and fro. "I used to be like that: a goofball, all this energy. Now... I don't know."

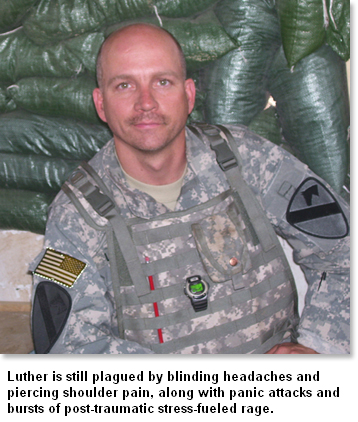

Some nights he doesn't sleep. Others he's back in Iraq, in the aid station, in endless isolation. The blinding headaches and piercing shoulder pain still plague him, he says, along with panic attacks and bursts of post-traumatic stress-fueled rage. Luther broke four bones in his hand punching a hole in his bedroom wall. His family's hallway is pocked with holes from similar incidents.

"He's not the man I married," says Nicki Luther. "And when I'm honest with myself, I don't think I'll ever have that man again. He wakes up screaming in the middle of the night, sweating, swearing." Nicki says he tries to be a good dad to their kids. "He used to wrestle around with them. But his body's like an old man's now. And he's so quick to anger. The kids say, 'We want our dad back.' I don't know what to tell them."

Three years after the mortar blast, Luther's life is still on shaky ground. Some days he's posting love notes on his wife's Facebook page and hand-delivering her favorite salad to her office at lunchtime. Another day, in the midst of an argument, he knocked down a family photo, then ripped the furniture out of the living room and dumped it in the garage, scaring his children. Soon after the birth of their fourth child, Marlee Grace, Luther and his wife separated. They reunited a few months later, in time for their eighteenth anniversary.

Luther knew he needed help. This time he sought it outside the military. He began seeing Troy Daniels, a psychologist, once a week. One fact was clear immediately, says Daniels. "He did not have personality disorder. The symptoms we were looking at looked more like traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder. To take a soldier having problems with vision, hearing and so forth—and to say he has personality disorder—that's a bogus kind of statement. I don't even think a master's student would make that kind of mistake."

While Daniels dismisses the Army doctors' diagnosis as a "gross error," he says he was not surprised by it. "I've treated hundreds of soldiers over the years, and I've seen a dozen personality disorder diagnoses. None of them," says the psychologist, "actually had personality disorder."

Yet all of those soldiers, he says, faced serious repercussions because of their discharge. "Many of the soldiers can't get hired anymore. Every time they go for a job, they'll have this paper that says they've been diagnosed with a personality disorder. Employers take one look at that and think, 'This guy's crazy. We can't hire him.' For most of the soldiers," says Daniels, "it becomes a lifetime label."

Luther luckily has secured a job, as a truck driver for Frito-Lay. Securing benefits has proved a bit tougher. Since being released from the Army, the sergeant has been locked in battle with the VA, fighting to prove that despite his PD discharge, his wounds are war related and thus worthy of disability and medical benefits.

Those efforts stumbled at first. In May 2008 the VA declared Luther "incompetent" and demanded that a fiduciary collect any disability benefits he may receive. Eventually, following a slew of paperwork and medical exams, the sergeant re-established his full standing. This past December—after VA doctors found Luther to be suffering from migraine headaches, vision problems, dizziness, nausea, difficulty hearing, numbness, anxiety and irritability—the VA cited traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder and declared Luther 80 percent disabled. "PTSD, a consequence of the TBI," wrote one VA doctor, "is a clear diagnosis."

The VA rating cleared the way for the sergeant to receive disability benefits and a lifetime of medical care. But it hasn't changed the Army's view—or altered Luther's discharge papers, which still list the sergeant as suffering from personality disorder. The sergeant, in return, has refused to pay back the $1,500 of his signing bonus that the Army says he owes, despite threats to garnish his wages. "I told them, Let me put it this way: as long as I'm breathing of my own free will, I'm not paying you a dime."

Luther says what really boils his blood is having to accept that his military career is over while the careers of those who devised his discharge are flourishing. After Luther's dismissal, Wehri, a captain at the time, was promoted to major and selected to be an executive officer with NATO. Dr. Dewees returned to Kentucky, where he continues to serve with the National Guard. Social worker Applewhite is now an instructor at Fort Sam Houston, where he teaches a class on how to identify mental disorders.

With or without the Army, Luther says he will continue to serve. With his health gradually improving and the bulk of his battle over, the sergeant is taking on a new mission: fighting the military on behalf of other soldiers like himself. Luther is now the founder and executive director of Disposable Warriors, a one-man operation that assists soldiers who are fighting their discharge and veterans who are appealing their disability rating.

Luther's organization did not receive a hero's welcome. Soon after founding the group, he discovered a threatening note on his windshield. "Back off or you and your family will pay!!" it read, in careful, black ink cursive. Weeks later, thieves broke into the home of a veterans' organizer who worked closely with Luther, taking nothing but the files of the soldiers they were assisting.

The sergeant, characteristically, is undaunted. "This is the right path for me," he says, his voice resolute. "I got to be there for these other soldiers. I'm not the only one who needs help."

|