asserting that Sullivan's organization didn't represent the nation's wounded vets and had no standing to demand an overhaul of a $94 billion government organization.

Judge Conti disagreed. The 86-year-old World War II veteran scheduled the trial for the end of April, and he demanded VA's top officials appear and take the stand. Over seven days VCS's lawyers would press them to explain internal e-mails and studies, statistics and videos, all suggesting that high-ranking officials purposely deceived Congress and the public, twisted data to cloak the VA's poor care of the ill and injured, and fired a prominent doctor who decided to expose the problems.

The Firing of Dr. Murphy

April 24, the fourth day of the VA trial. A crowd of wounded veterans sits in the San Francisco Federal Courthouse in stunned silence. On the courtroom's TV screen, a woman is explaining how her career fell to pieces. There is an unmistakable look of defeat on her face. As she pushes forward in her testimony, she slumps a bit in her white-striped pantsuit, and her voice begins to crack.

Dr. Frances Murphy had been one of the VA's shining stars. In 2004 she helped draft the Mental Health Strategic Plan, a blueprint for overhauling the VA. The plan called for 265 changes to the organization, among them: installing a tracking system to stay in touch with suicidal veterans, creating rehabilitation programs that involve veterans' families and streamlining the benefits process to resolve wounded veterans' immediate needs.

The plan was hailed by military leaders and veterans' groups. VA officials extolled it to reporters and members of Congress, citing it as proof of the organization's rapid transformation.

There was just one problem: the VA had done little to put the plan into practice. A recent Inspector General report found that 70 percent of VA facilities don't have a system to track suicidal veterans. Only a handful of VA hospitals have rehab programs that include families. And soldiers injured today face a benefits waiting list more than 650,000 veterans long.

Dr. Murphy knew it. She decided to speak out. And she had the perfect platform to do so: on March 29, 2006, almost two years after the plan's release, a group of prominent mental health organizations asked the doctor to address them in Washington. Following her speech, she would be given the Leadership in Government Award before an audience of high-profile figures: Senator Ted Kennedy, Surgeon General Richard Carmona, 60 Minutes's Mike Wallace and former First Lady Rosalynn Carter.

Dr. Murphy was blunt. Right now, she said, wounded veterans must climb over "a number of barriers" to receive their benefits. "It can be very confusing for veterans and family members to understand the services available to them and to navigate the systems." The VA promises veterans high-quality care. But "the promise of our state-of-the-art programs and scientific research is a hollow one if veterans who are struggling with the aftermath of severe trauma do not have equitable and timely access to quality mental healthcare near their homes. In some communities, VA clinics do not provide mental health or substance abuse care—or waiting lists render that care virtually inaccessible."

Dr. Murphy's portrait of the VA was dramatically darker than the official version put forward by the organization's other top officials. As recently as March 2007, as waiting lists surged, Dr. Michael Kussman, head of the VA's health department, stepped before a Congressional committee and said, "We are ideally poised to be able to take care of the patients as they transition out" of the Army.

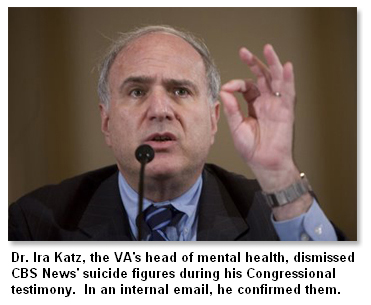

Dr. Kussman's comments meshed well with the warmer depiction of the VA put forward by Dr. Ira Katz. Katz, the VA's head of mental health, has become a key spokesman for the organization in recent years, underlining its success with the wounded and suicidal. With an MD and a PhD, soft speech and a gentle lisp, Katz has the credentials and the demeanor to paint a convincing image of a thriving VA.

In July 2007, after The Nation revealed that military doctors were purposely misdiagnosing soldiers wounded in Iraq as being mentally ill, the VA tapped Dr. Katz to appear before the House VA Committee and explain. The doctor had assuring words for the disgruntled legislators. "We have seen the press reports about that happening and are very concerned about those tragedies," he said. Dr. Katz said VA officials felt a "paternal" devotion to veterans' care and were committed to improving "the quality of care as well as access to care."

In November Dr. Katz was on camera again, this time on CBS News. Reporter Armen Keteyian had produced a groundbreaking report on veteran suicides. His five-month investigation found that in 2005 alone, more than 6,250 soldiers had committed suicide — 120 deaths each week, eighteen suicides every day. Again, Dr. Katz was reassuring. "We are determined to decrease veteran suicides," he told Keteyian. But "there is no epidemic of suicide in the VA."

Keteyian's report sparked a second Congressional hearing. There Representative Steve Buyer, a Republican from Indiana, pressed Dr. Katz to explain his views. Dr. Katz used the opportunity to publicly attack CBS's suicide figures. "Their number is not, in fact, an accurate reflection of the [suicide] rate," he told the committee.

Privately, however, the doctor's views were very different. In an internal e-mail written days after his testimony, Dr. Katz embraced CBS's findings as a flat fact. "There are about 18 suicides per day among America's 25 million veterans," he told Dr. Kussman. "[This] is supported by the CBS numbers."

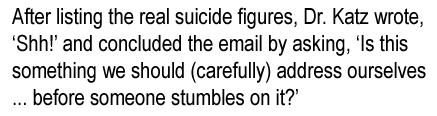

Three months later Dr. Katz returned to his computer, this time to express dire concerns about the growing number of veteran suicides. "Our suicide prevention coordinators are identifying about 1000 suicide attempts per month among the veterans we see in our facilities," he told his department's chief of media relations. It was information Dr. Katz did not want the public to see. He began the e-mail by writing, "Shh!" and concluded it by asking, "Is this something we should (carefully) address ourselves in some sort of release before someone stumbles on it?"

It was information the doctor didn't want Keteyian to find either. Dr. Katz titled his e-mail: "Not for the CBS News Interview Request." It was information the doctor didn't want Keteyian to find either. Dr. Katz titled his e-mail: "Not for the CBS News Interview Request."

Dr. Murphy was intent on taking a different path. Speaking to the mental health leaders gathered in Washington at the 2006 conference, she concluded her comments by highlighting the danger of creating ambitious plans, then failing to enact them. "Government likes to begin things, to declare grand new programs and causes," she told the audience. "But good beginnings are not the measure of success, in government or any other pursuit. What matters in the end is completion. Performance. Results. Not just making promises."

Days later Dr. Murphy was fired. A few weeks after that, the VA brought in a new official to be the public face of the organization: Dr. Ira Katz.

In the San Francisco courtroom, on the TV screen, Dr. Murphy's eyes are near tears. "[I was] very surprised," she says. She asked her boss to explain the VA's decision. He "chose not to answer that question." Dr. Murphy approached Dr. Kussman about other VA positions that had become available. "[Kussman] said he'd be happy to give me an early retirement."

'Jail or the Military'

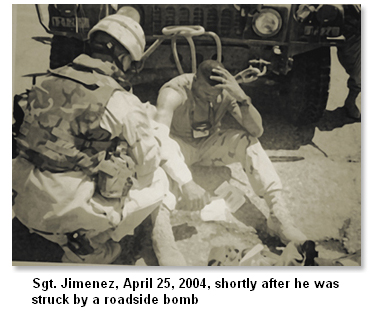

You might think that when soldiers return wounded from Iraq, it is assumed that they were wounded in Iraq. Not so. Under current VA policy, all soldiers have to prove that their wounds are the result of military service, even if they come home missing a leg or, like Sergeant Jimenez, with an arm heavy with shrapnel. Those who fail to make a convincing case cannot collect disability benefits.

To begin, veterans are asked to gather proof that they were wounded. The injured come to the VA carrying Purple Hearts and combat medals, folders thick with medical evaluations created in Iraq following their injuries. They are asked to provide the date and time they were wounded, to describe the circumstances surrounding the mortar or rocket blast. Veterans are often asked to contact those who witnessed the attack, to gather "buddy statements" that confirm the veracity of their stories.

"The system really pisses me off," says Bob Handy, chair of Veterans United for Truth. "These soldiers are seriously injured and emotionally traumatized, and when they get home, they make them jump through hoops to get their benefits." Handy's organization joined VCS in its lawsuit against the VA. He says he's especially disturbed by cases like Sergeant Jimenez's. "When you go into the VA with two Purple Hearts and X-rays show that you have shrapnel in your body, and you still can't get your benefits, that's punishing someone who's done a tremendous amount for this country."

VA spokeswoman Kerri Childress says the proof system is not meant as a swipe at soldiers. She says it's a standard mechanism to protect the VA from phony disability claims. "Veterans are human," says Childress. "Some are in desperate situations. Some have the choice of going to jail or the military. So a portion of them would commit fraud." If soldiers were no longer required to prove they are wounded, "it would be a travesty for veterans—an assault to the pride of honest soldiers when other vets scammed the system."

Eliminating the proof requirement would open the VA's checkbook to fraudulent claims, says Childress, which is why granting claims without investigation would be "an abdication of our responsibility to the taxpayer."

The wounded veterans who gathered at the San Francisco trial say they are sensitive to the VA's economic concerns. Still, Childress's words leave them cold. For many, her fraud explanation sounds like an echo of Col. Steven Knorr. Knorr, former chief of the Department of Behavioral Health at Evans Army Hospital, at Fort Carson, Colorado, gained notoriety last year when NPR's Daniel Zwerdling broadcast a memo Knorr had written. The memo, which Knorr posted on his office bulletin board, warned doctors not to take soldiers' descriptions of their ailments at face value. "We're not naïve, and shouldn't automatically believe everything Soldiers tell us," the colonel wrote.

Military leaders assured the public that Knorr's admonition did not reflect the military's views on treating physically or psychologically wounded soldiers, including those suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). As the commander of Fort Carson, Gen. Robert Mixon, told Zwerdling, "We expect leaders to support soldiers' getting care and treatment without bias. And if we see evidence of bias, we will take disciplinary action against the leaders." But Knorr was never disciplined. And as the San Francisco trial revealed, the fraud concerns present in Knorr's and Childress's statements fit squarely with VA policy. A baffled crowd of veterans watched as their lawyer read from Chapter Fourteen of the VA's official training guide. The guide urges doctors to track down documents from veterans' schoolteachers and families, people who knew them before they say they were traumatized. That "before and after" comparison is critical, says the guide, since the doctor may wonder "about the degree of distortion or fabrication in the interview. The clinical picture of PTSD is relatively easy to fabricate." Military leaders assured the public that Knorr's admonition did not reflect the military's views on treating physically or psychologically wounded soldiers, including those suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). As the commander of Fort Carson, Gen. Robert Mixon, told Zwerdling, "We expect leaders to support soldiers' getting care and treatment without bias. And if we see evidence of bias, we will take disciplinary action against the leaders." But Knorr was never disciplined. And as the San Francisco trial revealed, the fraud concerns present in Knorr's and Childress's statements fit squarely with VA policy. A baffled crowd of veterans watched as their lawyer read from Chapter Fourteen of the VA's official training guide. The guide urges doctors to track down documents from veterans' schoolteachers and families, people who knew them before they say they were traumatized. That "before and after" comparison is critical, says the guide, since the doctor may wonder "about the degree of distortion or fabrication in the interview. The clinical picture of PTSD is relatively easy to fabricate."

None of these issues were on Sergeant Jimenez's radar when he entered the West Los Angeles VA in 2005 seeking treatment and benefits. Jimenez carried proof of his Purple Hearts as well as medical documents inked in Iraq following the two roadside bomb blasts. Eventually he was checked into the facility for an overnight exam so VA doctors could monitor the seizures and sleep apnea that began after the blow to his head. There, with the clinicians watching, Jimenez had an epileptic attack.

His doctor put him on a powerful anticonvulsant, Gabapentin. The medication would mix with other VA-prescribed drugs: Prozac for depression, Prazosin for nightmares and Bupropion to help the sergeant sleep. Jimenez was hesitant to take so much medication. Still, he says, he was relieved the VA had finally recognized the effects of his traumatic brain injury.

His relief was short-lived. Five months after he filed for disability, Jimenez received a letter from the VA. The ratings officer handling his case said there wasn't sufficient evidence to prove that Jimenez had a seizure disorder. The rater further expressed doubt as to whether the sergeant had suffered a head wound at all while serving in Iraq, noting that reports of his traumatic brain injury were "based on an oral history." He suggested that Jimenez's health problems may be the result of a car accident twenty-one years ago in which he bumped his head on the steering wheel.

Jimenez's claim was denied and so was his request for disability pay.

"I couldn't believe it," he says. "The VA is saying I don't have seizures. But they watched me have a seizure. And they're giving me medication for it. It doesn't make sense." The VA also turned down his claim for chronic headaches. "Everything the VA doctors said I had, the VA rater turned around and said I didn't have."

Jimenez appealed. His appeal is pending.

Paul Sullivan, director of VCS, says all veterans face an uphill battle when seeking disability benefits. The reason, he says, is that there's a "power disparity between the VA and the veterans who are seeking benefits from the VA."

Veterans are not allowed to meet with the ratings officer who decides their case. In fact, the VA guarantees all its raters complete anonymity; veterans are never told who is judging their claim. Without a face-to-face visit or telephone conversation, raters make their decisions based solely on military documents and medical records.

Legally, raters are required to accept doctors' diagnoses. But in practice, some don't. As Jimenez learned, some raters substitute their own medical judgment, though they have no medical accreditation. Legally, raters are required to accept doctors' diagnoses. But in practice, some don't. As Jimenez learned, some raters substitute their own medical judgment, though they have no medical accreditation.

That fact haunted Jimenez, especially after his seizure and headache claims were rejected. The sergeant wonders whether his rater would have changed his mind and accepted his doctor's diagnosis if only he had seen the scars on Jimenez's face and talked with him for a minute or two about what it's like to wake up in the middle of the night, petrified and wet with your own urine.

Many veterans say their greatest frustration is much simpler: they would like to pay a lawyer to make their case for them. Current VA regulations bar them from doing that. The prohibition on hiring a lawyer traces its roots to the 1860s, before the modern VA was established. The Lincoln Administration was concerned that lawyers would charge vulnerable Civil War veterans exorbitant fees for filing their disability papers. To stave off the lawyers, the government barred soldiers from paying them more than $10, effectively eliminating them from the process.

Today, says Childress, the VA's reasoning is slightly different. The ban is meant to level the playing field for impoverished soldiers. "Allowing veterans to have lawyers would be unfair to the vets without money," she says. Wealthy veterans would have high-priced lawyers and could potentially collect more benefits. "We care about indigent veterans, so we decided to keep the regulation in place."

The result is that all veterans have to fill out the twenty-six-page disability application on their own. The application is loaded with charts and legal jargon, requests for dates when the veteran was injured, the locations where he was treated, his family and employment history, questions about his pension and readjustment pay, and inquiries as to the aggregate value of the veteran's spouse's mutual funds, along with her Social Security number, the name of her previous husband and the location of their wedding. There's also a large space for an essay on the veteran's military and medical history.

James Terry, chair of the VA's Board of Appeals, says the application isn't terribly complicated. "I have a PhD," he says, "but even if I only had a third-grade education, I think I could fill out the form."

But Sullivan says the application has proved a significant obstacle for many members of his organization, especially those who are brain damaged due to combat or haven't had a good night's sleep in months due to PTSD. "What's happening is that many veterans are saying, 'Aw, forget it' and not filing a claim," says Sullivan. "That really concerns us because these are the guys who need the benefits the most."

Human Time versus VA Time

April 28, the fifth day of the VA trial. On the stand this morning is Michael Walcoff, one of the VA's top officials. He is facing sharp questions about how long it takes to get benefits to wounded veterans. Walcoff begins his two days of testimony with calm, confident words, but as the questions grow more pointed, the deputy under secretary starts to stammer and stumble.

Walcoff is having a particularly tough time defending a key VA statistic: that when a wounded veteran applies for benefits, it takes the VA an average of six months to process the claim. That figure has made many veterans' leaders angry. Bob Handy of Veterans United for Truth says the VA should be ashamed of making wounded veterans wait six months to find out whether or not they'll receive disability benefits. But the VA sees the statistic a bit differently. The organization has been aggressively promoting the six-month figure as a sign of progress, an improvement from 2001, when veterans faced a wait of seven and a half months.

In February 2006, Daniel Cooper, then head of the VA's benefits department, told the House VA Committee about the organization's six-month processing time. Two years later, VA officials returned to Capitol Hill with the same statistic. Patrick Dunne, the acting under secretary for benefits, told the Senate VA Committee, "In Fiscal Year 2007 our average processing time was 183 days," or 6.02 months.

To Elinor Roberts, the number sounded wrong. Roberts is a director at Swords to Plowshares, a nonprofit organization that guides low-income veterans through the VA process. "I've been working with veterans for fifteen years, and I'll tell you, six months to process a claim—that would be warp speed." Roberts says the majority of the veterans she has worked with have waited "significantly longer." Like many others at the trial, she wanted to know how the VA calculated that figure.

From the witness stand, Walcoff explains. The VA does take an average of six months to complete a claim. But it depends on what you consider a "claim." By "claim," the VA is referring to both disability claims and pension claims, which take significantly less time. Internal VA documents show that some pension actions can be completed in less than an hour. Those rapid resolutions provide a counterbalance to more complicated claims, like a PTSD disability claim. A recent report from the Government Accountability Office shows that PTSD claims often take longer than one year.

Walcoff admits that including pension claims in the mix does lower the overall "claims average," but he says combining the two is not meant to deceive. It is simply that the VA has never isolated one set of claims. "We've always lumped them together," he says.

Completing a claim in six months also depends on what the word "complete" means. For thousands of veterans, filing a claim and receiving the VA's response is just the first step in a much longer journey toward collecting their benefits. That group includes veterans who decide to appeal the VA's decision. Like Sergeant Jimenez, they are upset that the VA rejected their claim or that the organization labeled their injury as a minor health issue and gave them a low disability rating. Ratings, from 0 to 100 percent disabled, dictate how large veterans' disability checks are and whether they are eligible for a lifetime of VA medical care.

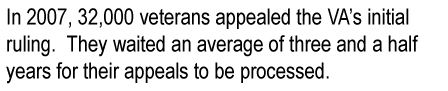

In 2007, more than 32,000 veterans appealed the VA's initial decision. Those soldiers waited an average of three and a half years for their appeals to be processed, in addition to the six-month wait for the initial decision.

Asked to explain the three-and-a-half-year delay, Walcoff seems at a loss. He notes that appeals cases can be complex and that the VA has placed a greater focus on handling initial claims. "I wish I could say to you that that fully explains why it takes [so long], but I can't," he says. "This is an area that we have got to do better on."

When a veteran's claim is denied, the VA appeals board has the ability to reverse the decision. It also has the power to boost a veteran's disability rating. At other times the appeals board takes a third route: if the board sees an error in the paperwork, it can send the veteran's case back to the local VA that decided it the first time and demand that the local office do its work again. Returning the veteran's case to the local VA gets the claim fresh consideration. But it also means that essentially the veteran is back at square one. For wounded veterans in immediate need of benefits, having to pass through the entire system again can be a great strain.

This strain, however, doesn't appear in the VA's statistics. That's because, in calculating its decision time, the VA counts only a veteran's first pass through the system. Sullivan says some of the vets in his organization were rushed through the initial decision process in about three months. Then after their cases were returned to the local VA, it took about nine months to decide their claims the second time. A case like that, notes Sullivan, leaves the veteran waiting twelve months for benefits, but it lowers the VA's six-month average, since the organization counts only that first three-month pass through the system.

As Walcoff's testimony continues, his voice softens. He says he's aware of how long it takes to process a case. "These are not numbers that I'm particularly proud of," he says. Still, he insists the VA is taking action to speed the process. With a surge of excitement in his voice, Walcoff begins to describe a new VA program: Benefits Delivery at Discharge.

The BDD program allows wounded soldiers to submit their disability claims to the VA before they are officially discharged from the Army. Under BDD, soldiers can submit their claims six months before they leave the Armed Forces. "The idea here is that when a veteran knows that he is going to be getting out of the service and knows that he is going to be applying for benefits, why not take the application for benefits from him while he's still in the service, with the idea that when he becomes a veteran, we'll be able to pay him quicker," says Walcoff. "This is a program that we very much encourage." The BDD program allows wounded soldiers to submit their disability claims to the VA before they are officially discharged from the Army. Under BDD, soldiers can submit their claims six months before they leave the Armed Forces. "The idea here is that when a veteran knows that he is going to be getting out of the service and knows that he is going to be applying for benefits, why not take the application for benefits from him while he's still in the service, with the idea that when he becomes a veteran, we'll be able to pay him quicker," says Walcoff. "This is a program that we very much encourage."

The VA has been expanding the program at lightning speed. In 2007 more than 28,300 soldiers applied for benefits through BDD. This year the VA is on track to collect more than 43,000 claims through the program. It has been a boon for soldiers seeking rapid benefits.

It has also become a way for the VA to further skew its discharge figures. Under cross-examination, Walcoff admits that when the VA calculates the time it takes to process a claim, it treats BDD soldiers a bit differently. Normally the organization starts its clock when it receives a claim. With BDD soldiers, says Walcoff, the VA starts the clock when the soldier is discharged. When a soldier submits a claim six months before he leaves the Army and the VA takes six months and a day to process his claim, VA officials record the processing time as one day.

Why does the VA do this? "It was an oversight," Walcoff tells the veterans' attorney. "I mean, there was nothing intentionally that we were trying to hide." The deputy under secretary looks the lawyer in the eyes. "When you brought it up," he says, "that's the first time I thought of it."

Walcoff's testimony ends with a gruesome coda. He acknowledges that while a veteran's claim is pending, there is a way he can bring his case to a close: he can kill himself. For VA statistical purposes, a death is recorded as a "resolved" claim. Death "is a form of resolution," says Walcoff, but "it's certainly not the form that we want to see." When veterans die early in the claims process, their cases provide the VA with especially deceptive figures.

When veterans wait four or five months for disability benefits, then take their own life, family and friends often point to the VA for failing to provide care. But on paper, cases like that improve the VA's image. They are claims "resolved" in less than six months, further lowering the VA's average processing time.

After Walcoff is dismissed, the court takes a recess. Veterans spill into the hallway, shaking their heads and joking with one another about the VA's "six-month" processing time. "It just goes to show," says one veteran, "there's a real difference between human time and VA time."

'The Next Group of Guys'

July 4. Sergeant Jimenez wakes up and checks his e-mail. There is a message waiting for him from Paul Sullivan. Judge Conti's decision has come in. The news isn't good. July 4. Sergeant Jimenez wakes up and checks his e-mail. There is a message waiting for him from Paul Sullivan. Judge Conti's decision has come in. The news isn't good.

In his ruling, Conti calls the VA's current performance "troubling." He says the "Plaintiffs have demonstrated that their members have suffered injuries in fact. As testified to at trial, their members have faced significant delays in receiving disability benefits and medical care from the VA." Given the "dire consequences many of these veterans face without timely receipt of benefits or prompt treatment for medical conditions... these injuries are anything but conjectural or hypothetical."

And yet, writes Conti, there is little he can do. While the structural changes suggested by Sullivan's organization "would likely result in the amelioration of the injuries," he is in no position to force those changes upon the VA. "The remedies sought by the Plaintiffs...would call for a complete overhaul of the VA system, something clearly outside of this Court's jurisdiction."

The ruling angered Jimenez. "I don't understand it," he says. "If he recognizes the problem, he should do something about it."

Sullivan and his lawyers have appealed. Their case is pending before the Ninth Circuit. In the meantime, Sullivan has been working to raise awareness of the case, reaching out to other veterans' leaders and to members of Congress.

"I was disappointed at the outcome of the lawsuit," says Representative Bob Filner, chair of the House VA Committee. The Democrat from San Diego followed the case closely. He says the suit was "a creative way to bring attention to the fact that the VA is not doing its job. Constitutionally the judge is probably right: overhauling the VA is the executive branch's and Congress's job. But we haven't been doing it."

Filner says that had Judge Conti sided with the veterans, "it would have given us a lot of leverage" to make changes to the VA. As it is, "we're going to keep plugging along and doing what we can."

Jimenez, meanwhile, is working to get his life in order. His marriage collapsed when he returned from Iraq, under the weight of his sickness and suicidal depression. The 39-year-old is still adjusting to life on his own, in Yucaipa, California, an hour and a half from his four young children. He is also still clashing with the VA. Recently he had an appointment with his VA psychiatrist. When he arrived at the Loma Linda facility, he was turned away and told the doctor would not be coming in that day.

The sergeant has convinced the VA of some of his injuries. He is now receiving benefits for sleep apnea, chronic dyspepsia, PTSD and tinnitus. But the organization still believes his seizures and brain injury are unrelated—and insists caffeine is a key culprit in his ills.

That kind of logic, says Jimenez, reminds him why the Conti ruling is such a disappointment. "I wanted the system to get fixed," he says, "not for me or other soldiers in the lawsuit but for the next group of guys, so when they come back from Iraq, they won't be overlooked."

|